Weekly Top 10 Newsletter by Daniel Tsvetanov

Gazprom’s subsidiary South Stream Transport B.V. and the Swiss-based company Allseas Group S.A. signed a contract to build the second string of the Turkish Stream gas pipeline’s offshore section.[1] The deal was signed on 21 February, 2017, in Amsterdam; it complements the previous agreement of building the first string of Turkish Stream project.[2]

The Turkish Stream project is aimed to provide gas supplies to the Turkish market and the Southeast European market across Black Sea, bypassing Ukraine, where the transit contracts expire in the beginning of 2020. The construction of the first string began in December 2016, and it is intended for Turkish consumers, while the second string will deliver gas to Southern and Southeastern Europe. Each string of the Turkish Stream will have the capacity of 15.75 billion cubic meters of gas per year. Although it seems logical and commercially viable to build the two strings simultaneously, Gazprom does not yet have a clear answer from Brussel, whether Europe agrees to open its market to additional Russian gas supplies. In the absence of clear position of the European Commission, it may be a wise decision to put the second string on hold.

Turkish Stream II: to Turkey or Bulgariya?

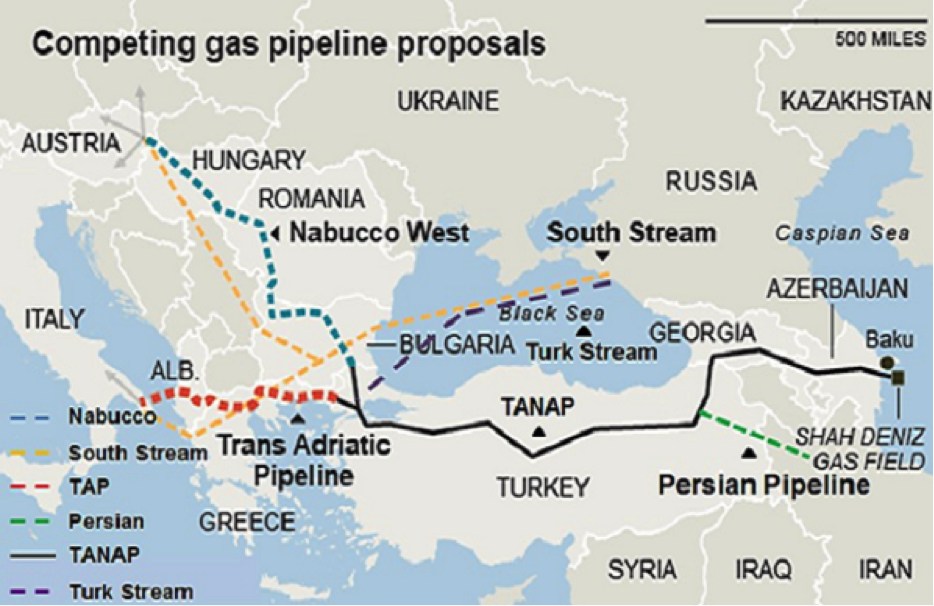

Currently, there are three options to consider for the Russian natural gas heading towards Europe – see Figure 1 for some orientation. The most efficient and secure route for the second string will be if it is build directly to Bulgaria, as it was planned previously within the South Stream project (a project suspended back in 2014[3]). During a business forum in Varna, Bulgaria on 15th February, Igor Ilingin, the Russian attaché on trade of the Russian Federation in Bulgaria, hinted that there are still possibilities for Sofia to become a hub for Russian gas.[4] There is still no answer from Bulgaria, because there are Parliamentary elections on 26th March and it is uncertain what will be the position of the new government. Despite the political developments in Bulgaria, the final word will have to come from Brussels.

The second option suggests that both strings will land at the Turkish coast. This scenario seems less advantageous for Russia, because the role of Turkey as a transit state will increase and prices of natural gas deliveries for the European market would be affected by additional transportation costs. Whether the second string is build to Turkey or Bulgaria, Brussels have to state its position and so far there are no signs of agreement or disagreement.

Figure 1. Competing gas pipelines proposals Source: Kisacik and Kaya[5]

Considering these two possibilities, none of them seems viable – there is no positive response from Brussels. Brussels is looking for a way to achieve diversification of natural gas suppliers for the South East region, given the current high dependence of Russian supplies.

Russian gas as a pillar of competitive European gas market: the third option

Reliable opportunity to pursue this goal is the Trans Adriatic Pipeline project (TAP), which will deliver natural gas from Azerbaijani’s Shah Deniz II field via the Trans-Anatolian Pipeline (TANAP) through Turkey. TAP will be connected to the TANAP on the Turkish-Greek border and it will run through Greece, Albania, the Adriatic Sea and Italy. The project is currently in its construction phase, which started in 2016 and the estimate capacity will be 20 billion cubic meters of natural gas annually. According to the Third Energy Package, gas from Shah Deniz II can provide only 50% of the pipeline capacity (10bcm/a) and any other gas supplier can bid for the other 50% of capacity through so-called “Open Season” auctions.

This third option provides a key for Gazprom to unlock a new supply route: Russian gas can find its way to Europe via the second string of Turkish Stream if Gazprom bids for the spare capacity of TAP.

Overall, Gazprom demonstrates flexibility and readiness to pursue its goal to bypass Ukrainian gas deliveries for the region in time. At the same time, it seems like more Russian gas, despite some worries in Brussels, might be exactly what is needed for truly competitive market in South East Europe and beyond.

[1] Gazprom agrees with Allseas Group for constructing second string of TurkStream’s offshore section. Pipeline Oil and Gas Magazine, February 22, 2017. https://www.pipelineme.com/news/international-news/2017/02/gazprom-agrees-with-allseas-group-for-constructing-second-string-of-turkstream-s-offshore-section/

[2] Priority Projects: Turkstream. Gazprom. http://www.gazpromexport.ru/en/projects/

[3] Jonathan Stern, Katja Yafimava, Simon Pirani. Does the cancellation of South Stream signal a fundamental reorientation of Russian gas export policy? Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, 2015. https://www.oxfordenergy.org/publications/does-the-cancellation-of-south-stream-signal-a-fundamental-reorientation-of-russian-gas-export-policy/

[4] Russian Trade Representative: South Stream is Possible. https://www.google.ru/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=11&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=0ahUKEwjknqbrnrrSAhUhJJoKHXAXDDQQFghIMAo&url=https%3A%2F%2Fdariknews.bg%2Fregioni%2Fvarna%2Fruski-tyrgovski-predstavitel-iuzhen-potok-mozhe-da-ima-no-samo-s-edna-tr

[5] Sina Kisacik, Furkan Kaya. The Implications of TANAP and Turkish Stream on the energy security after the recent Ukraine crisis. UPA, 2016. http://politikaakademisi.org/2016/01/13/the-implications-of-tanap-and-turkish-stream-on-the-european-energy-security-after-the-recent-ukraine-crisis/