By Alan Mamatov

Abstract: Starting from the second half of the 20th century, many researchers have focused their attention on the increasing influence of oil price shocks on global economic performance. However, the current stock of empirical literature significantly lacks research on developing oil importing economies from the post-Soviet region. The purpose of this paper is to empirically analyze the essence of the relationship between oil price shocks and economic growth in the specific case of the Kyrgyz Republic. Following an in-depth analysis of the macroeconomic structure of the country, it will be demonstrated that despite of the oil importing status of the Kyrgyz Republic, abrupt increases in crude oil prices may benefit the pace of its economic growth in the long-term, whereas abrupt decreases may not induce any visible impact.

Key words: Oil prices, price shocks, economic growth, Kyrgyzstan

For the last forty years, many researches have been devoting their attention to the increasing role of oil price fluctuations in global economic performance. Existing empirical inquiries can be characterized in accordance with the economies under consideration: oil importing and oil exporting. In turn, empirical results related to the impact of oil price fluctuations or shocks on real economic activity are found to be different in those two categories of countries.

Logically, an oil price increase should benefit oil exporters, but not oil importers, whereas an oil price decrease must positively impact oil importers, and not oil exporters. However, in reality the causal nexus might have a different essence. For instance, oil importing countries can absorb unfavorable effects of a negative oil price shock in light of different oil dependency pattern, different policies implemented, and different transmission mechanisms.[1]

The ways oil price fluctuations can affect the macroeconomic activity of developing oil importers pertain to both the supply and demand side of the economy. The aggregate supply side can be considered through the potential effect on the private production sector. For instance, if the price for crude oil (basic input) increases, it would lead to increase in production costs, which in turn lowers output. Assuming that a significant part of its gross domestic product (GDP) consists of an energy-intensive sector, a positive oil price shock would then decrease the overall welfare of the economy (ceteris paribus), i.e. reduce the pace of economic growth.[2]

In contrast to the supply side, an oil price increase might affect aggregate demand by altering the overall levels of consumption and investment. For an oil importing economy, it would cause consumption levels to fall as a result of a decrease in real disposable income. Investment levels would then be affected through the decreasing profitability of firms, which would make them less attractive from an investors’ perspective.[3]

Moreover, oil price shocks may alter currency exchange markets and the inflation rate, which would lead to indirect effects on real economic activity. The exchange rate (floating regime) might also absorb negative effects of oil price shocks, incidentally boosting indirect effects. Moreover, Central Banks may induce a tighter monetary policy to offset inflation, which could potentially lead to a change in the lending interest rate. The bottom line is that the overall economic activity of a developing oil importer would likely slow down after a sudden increase of the oil price.[4]

However, for certain small oil importing economies, there is a possibility that positive oil price shocks could induce an opposite effect on real economic activity. The reason for that might be the composition of GDP, the geographical position of the country, close economic relations with big oil exporting economies, or the influence of remittances on aggregate demand.

Additionally, results of certain inquiries conclude that the impact of oil price fluctuations on economic growth cannot be described via the conventional way of linear and symmetric specification.[5]

In contrast to most studies, which are generally focused on developed economies, the present research will assess the effects of oil price shocks on economic growth in the specific case of the small oil importing economy of the Kyrgyz Republic. In analyzing the dynamic interactions between oil price shocks and economic growth, special attention will be paid to the influx of remittances as a major transmission channel for indirect effects of abrupt oil price fluctuations.

Specifically, a multivariate vector autoregression (VAR) analysis will be applied on a monthly time series data set (covering the period from January 2005 until December 2015) to enlighten the way oil price changes might impact the real economic activity of the Kyrgyz Republic.

The Structure of the Economy of the Kyrgyz Republic and its Potential Response to Oil Price Shocks

The Kyrgyz Republic (or Kyrgyzstan) is a developing, landlocked economy in Central Asia. Prior to its independence in 1991, Kyrgyzstan was a part of the Soviet Union, an alliance which significantly determined its development also after the Soviet Union’s collapse. Currently, Kyrgyzstan is considered to be a low-middle income country, with the gross national income (GNI) per capita equaling to 1, 170 U.S. dollars (2015).[6]

After the end of the Soviet Union era, Kyrgyzstan suffered considerably from a large contraction in industrial output, a diminishing standard of living, and an overall recessionary pattern of national economy. The government tried to implement several neo-liberal reforms to smooth the transition from a centrally-planned to a free market-oriented type of economy. Among others, the government of Kyrgyzstan supported the mass privatization of state-owned enterprises, a rapid integration into international trade system, and a complete deregulation of the economy.[7]

The economy of the country was steadily developing until the national revolution of of 2005, which significantly diminished the growth capacity of the country, as well as its investment attractiveness. Five years later in 2010, Kyrgyzstan suffered from another political upheaval and national turmoil, which further worsened its development potential.[8]

From an international trade perspective, Kyrgyzstan, as a landlocked economy, is heavily dependent upon the trade relations with its closest neighbors, i.e. the Russian Federation, Kazakhstan, and China. |And indeed, for the last years, Kyrgyzstan’s major import sources have been China, Russian, and Kazakhstan with the most imported products being various textiles, refined petroleum, machinery and equipment.[9]

In the meantime, the countries to which it exports most are Switzerland, Kazakhstan and Russia. The largest amount of trade with Switzerland occurs because of the internal gold production. Concurrently, the prime exported products were precious metals, together with various textiles, agricultural products, and other ferrous metals.[10]

Addressing the composition of the GDP of the country for the last seven years directly, it is reasonable to state that the GDP of Kyrgyzstan has been heavily dominated by the service sector. In particular for the period of 2009-2015, the share of the service sector in the GDP of Kyrgyzstan was, on average, equal to 47 percent, while in 2015 it reached its peak value of 50 percent.

Figure 1: The GDP structure of the economy of the Kyrgyz Republic, 2009-2015

Source: Ministry of Economy of the Kyrgyz Republic, 2016. Sotsyal’no-ekonomicheskoe razvitie Kyrgyzskoy Respubliki. [online] Available at: <http://mineconom.gov.kg/index.php?Itemid=159&lang=ru> [Accessed 1 June 2016].

The second largest sector for the same period was the industrial sector, which on average accounted for 18 percent of the country’s GDP, whereas the third largest sector was the agricultural sector, which, on average, made up 16 percent of the GDP. Finally, the last sector of significance was the construction sector, which accounted for about 7 percent of the GDP.[11] The graphical information on the changes in the composition of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP for the period of 2009-2015 is presented in Figure 1 (see above).

Furthermore, it is necessary to mention the huge role that international remittances have in influencing macroeconomic performance of the Kyrgyz Republic. The population of Kyrgyzstan has experienced a massive external labor migration, since the beginning of 2000s. External labor migration was primarily determined by the low living standards and lack of job opportunities in Kyrgyzstan, as well as by the rapid economic expansion in neighboring Kazakhstan and Russia.[12]

Hence, Kyrgyzstan became the second largest remittance-receiving country in the world, where the remittances strongly determined the economic well-being and the quality of life of the majority of the population. The major part of remittances comes from labor migrants working in either Russia or Kazakhstan.[13]

Figure 2: Personal Remittances, as a share of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP, 2004-2014.

Source: The World Bank, 2016. World Development Indicators. [online] Available at: <http://databank.worldbank.org/data/reports.aspx?source=world-development-indicators&preview=on#> [Accessed 1 June, 2016].

Specifically, for the recent decade, the average value of remittances as a share of the GDP was equal to 22.5 percent, reaching its paramount value of 31 percent in 2013. More detailed information on the changes in the value of personal remittances as a share of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP is presented in the Chart 2 above.

The strong role of personal remittances, as well as the firm trade relations with Russia and Kazakhstan (both are considered pure oil exporting economies), might significantly alter the way crude oil price shocks would affect the real economic activity in the Kyrgyz Republic.

Taking into consideration the structure of the economy of Kyrgyzstan, its GDP composition, geographical constraints, close economic ties with Russia and Kazakhstan, and huge influx of remittances from aforesaid countries, the transmission mechanisms through which oil price shocks might impact the economic growth of Kyrgyzstan might drastically differ from what would be considered from conventional perspective.

For example, an abrupt decrease of the oil price might not directly benefit the real economic activity in the Kyrgyz Republic due to the country’s GDP structure, which is heavily dominated by the service sector. The service sector is usually regarded as considerably less energy-intensive than light or heavy industries.

Furthermore, a sudden decrease in the crude oil price should negatively impact the real economic activity of Kyrgyzstan’s close neighbors, i.e. Russia and Kazakhstan, due to their oil exporting nature. A Curtail in real economic activity of Russia and Kazakhstan, in turn, would diminish the aggregate amount of remittances that flows to Kyrgyzstan from its labor migrants. That, of course, would induce a significant negative demand shock to Kyrgyzstan’s population that heavily relies upon personal remittances.

Moreover, an adverse impact of an abrupt decrease in crude oil price on the economic growth of Russia and Kazakhstan might entail a negative growth spillover effects on the economy of Kyrgyzstan, due to the country’s landlocked nature.[14] The overall outcome should thus be an indirect slowdown of real economic activity in the Kyrgyz Republic, resulted from a negative oil price shock.

In case of a positive oil price shock, the sequence of events might take an opposite nature: the economies of Russia and Kazakhstan would benefit from a sudden increase in crude oil prices, while the economy of Kyrgyzstan might not suffer a lot, due to the composition of the country’s GDP.

Economic expansion in Russia and Kazakhstan would possibly increase the influx of remittances from Kyrgyzstan’s labor migrants, as well as enhance the positive growth spillover effects. The aggregate outcome would then be an indirect enhancement of the real economic activity in the Kyrgyz Republic, resulting from a positive oil price shock.

The Empirical Analysis

In order to empirically examine and verify the nature of the relationship between oil price shocks and the economic growth of Kyrgyzstan, as well as to determine the role of remittances in the aforesaid interaction, the vector autoregression (VAR) analysis was chosen to be employed.

Christopher A. Sims firstly proposed the multivariate VAR methodology in the context of structural macroeconomic analysis. The VAR approach introduced by Sims allowed the investigation of the stochastic behavior of macroeconomic indicators in the framework of the dynamic systems, alleviating common constraints on parameters.[15]

The system of VAR equations is commonly represented in the Moving Average form, ensuring applicability of the impulse response functions and forecast error variance decomposition analyses:[16]

The set of variables were chosen upon the works of previous scholars. Specifically, the description of the model and the key variables were borrowed from the work of Jiménez-Rodríguez and Sánchez,[17] with the inclusion of the appropriate modifications necessary to test the proposed hypothesis.

In particular, the model incorporates three key variables of interest: crude oil prices, the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic, and the monthly influx of remittances. These are included in order to examine the previously mentioned hypothesis and trace the impact of shocks in the crude oil price on the real GDP of Kyrgyzstan and inflow of remittances.

The crude oil price variable is represented by the monthly changes in the Brent spot crude oil price, taken as U.S. dollars per barrel. The spot price for Brent crude oil is considered to be one of the leading global benchmark prices of crude oil, and was extensively used by researchers previously.[18]

The real GDP of Kyrgyzstan is used as a proxy for economic growth, while remittances are added to control for the crucial transmission mechanism, through which changes in crude oil prices might induce demand shock to the economy of Kyrgyzstan (both real GDP and remittances are expressed in natural logarithms, the first differencing of which allows to perceive variables in terms of growth rates).

Moreover, there are several additional control variables that are included to the model to account for other potential transmission mechanisms.[19] Kyrgyzstan’s net imports of energy products are added to control for trade distortions that may arise from sudden changes in crude oil prices for instance.

As was mentioned previously, Kyrgyzstan is a landlocked economy, implying a strong dependence upon the trade relations with close geographical neighbors. The Russian Federation and the Republic of Kazakhstan, the largest economic partners of the Kyrgyz Republic and its closest neighbors, are quite sensitive to the sudden hikes in oil prices, due to the oil-exporting nature of their economies.

Thus, oil price fluctuations might impact the real economic activity of Kyrgyzstan through negative or positive growth spillover effects. In turn, it is likely to be translated through changes in net imports of energy products of the Kyrgyz Republic, due to the oil-importing nature of Kyrgyzstan’s economy.

Additionally, the real effective exchange rate and the inflation rate are added to the system in order to control for other crucial transmission channels through which oil price fluctuations might indirectly impact the economic growth of Kyrgyzstan.[20]

Lastly, the crude oil price variable will further be transformed into two separate variables in order to capture the potential non-linear relationship between oil price shocks and real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic. Particularly, the asymmetric transformation of the oil price variable will have the following form:[21]

The data sample on each variable is comprised of monthly data and covers the period from January 2005 to December 2015. The total number of observations is equal to 132.

The data points on real GDP and the inflation rate originate from the official archives of the National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic. The real GDP is measured in millions of soms (the domestic currency of Kyrgyzstan) and adjusted for the monthly inflation rate.

The data points on the monthly influx of remittances, the real effective exchange rate, and the net imports of energy products come from the online statistical database of the National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic (the subsection named “external sector of the economy” contains the data on the aforesaid variables).[22] The data on the Brent spot crude oil price originates from the database of the U.S. Energy Information Administration (the section named “Spot Prices for Crude Oil and Petroleum Products”).

In particular, monthly influx of remittances and net imports of energy products are represented in millions of the U.S. dollars. For the real effective exchange rate the base period is the year of 2010. Moreover, the real effective exchange rate is adjusted to the basket of ten significant foreign currencies, among which the U.S. dollar, the euro , the Russian ruble, the Kazakhstani tenge, the Chinese yuan, the Japanese Yen, the Turkish lira, and other regional foreign currencies.

As previously stated, five out of six variables were transformed to the natural logarithmic form to be able to produce inference in terms of elasticities. The inflation rate was not transformed to the natural logarithms, due to the fact that it was already represented in the form of percentage changes in the CPI.

It has to be noted that several statistical procedures were performed on each variable from the chosen data set, in order to ensure stationarity of the stochastic processes and eliminate the possibility of co-integration among time series variables.

In particular, augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) and the Phillips-Perron (PP) unit root tests were performed on each variable of the model. Under each testing procedure it was verified that variables of the proposed model are first difference-stationary variables or integrated of order one, implying that first differencing is sufficient to achieve stationarity of the stochastic processes.

The potential presence of co-integration among stochastic variables was tested through the Søren Johansen’s (1995) test for co-integration.[23] The results of the test clearly indicated the absence of co-integration among tested variables, thus solidifying the validity of the proposed VAR model.

Finally, the likely occurrence of residual autocorrelation was verified through the Lagrange-multiplied test, which demonstrated no autocorrelation in residuals for constructed model, whereas the lag-order selection statistics was based upon the Akaike information criterion.

The Macroeconomic Effects of Oil Price Shocks

Based upon the previously established VAR methodology, it is possible to extend the verification of the proposed hypothesis through the impulse-response functions (IRFs) analysis.

In particular, the present study relies on the results of cumulative IRFs, which allow tracing the accumulated response of a certain endogenous variable to a unit exogenous shock in another endogenous variable within the dynamic system of VAR equations.[24] The vertical axis in each IRF graph represents a percentage change in a response variable. The horizontal axis, in turn, displays the time path of a response variable, where each step equals one month. Shaded areas represent two standard error bands of the 95 percent confidence interval.

To justify the application of the IRFs analysis, the series of the Granger-causality Wald tests were implemented. Formally, “a variable X is said to Granger-cause a variable Y if, given the past values of Y, past values of X are useful for predicting Y”.[25]

The results from the Granger-causality Wald tests determined that in a model with positive oil price changes, the real GDP is Granger-caused by both positive oil price changes and remittances. The remittances variable, in turn, was Granger-caused only by positive oil price fluctuations.

Thus, for the first model it is necessary to analyze the impact of one percent of positive oil price shock induced on the response paths of the real GDP and remittances variables. Additionally, it is possible to trace the impact of one percent positive shock in the influx of remittances induced on the real GDP.

Figure 3 demonstrates the accumulated response of Kyrgyzstan’s real GDP to one percent positive oil price shock. As one may observe from the graph, the first reaction of Kyrgyzstan’s real GDP to a sudden change in oil price is negative.

Particularly, in one month after the shock, the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic would decrease by approximately 0.182 percent. This negative pattern would remain until the fourth month, and the decrease in real GDP in four months after the shock would be equal to approximately 0.025 percent.

Yet, after the fourth month, the real GDP exhibits a steady positive growth pattern. Specifically, in six months after the positive oil price shock, the real GDP of Kyrgyzstan would increase by about 0.311 percent. In ten months after the one percent positive oil price shock, the accumulated effect is even more pronounced, indicating the increase in real GDP of Kyrgyzstan by about 0.501 percent.

After tenth months, the cumulative impact of positive oil price shock on the real GDP of Kyrgyzstan would drastically diminish, implying that the effect eventually dies out. In twelve months, the one percent positive oil price shock would induce only 0.204 percent amplification in the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic.

Figure 4 indicates the impulse-response path of the influx of remittances variable to one percent positive oil price shock. As one may observe from the graph below, a positive oil price shock induces a steady increase in the influx of remittances to the Kyrgyz Republic.

In particular, one month after the shock, the remittances’ inflow would increase by about 0.183 percent. With a minor decrease in a third month, the influx of remittances demonstrates a firm upward trend up until the fourth month. After the fourth month, the effect of a shock eventually stabilizes, indicating a permanent nature of the induced impact.

Figure 3: Accumulated impulse-response path of the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic to one percent positive oil price shock.

In four months after the shock, the cumulative amplification in remittances would be the highest, equaling approximately 0.551 percent, whereas in twelve months, the remittances would increase approximately by 0.497 percent.

Figure 4: Accumulated impulse-response path of the influx of remittances to one percent positive oil price shock.

Finally, Figure 5 represents the accumulated response of Kyrgyzstan’s real GDP to one percent positive shock in the influx of remittances. As one may observe from the graph below, initially the real GDP responds positively to the sudden increase in the remittances’ inflow. In particular, one month after the shock the real GDP of Kyrgyzstan would sharply increase by about 0.087 percent.

However, after the first month, the accumulated impulse-response path of the real GDP demonstrates a steadily diminishing pattern, indicating that the impact of one percent shock in remittances induce a rather short-run nature.

In three months after the shock, the real GDP would increase only by about 0.037 percent, while in six months after the shock, the positive impact of an increase in remittances is almost negligent, equaling to a 0.006 percent amplification in the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic. In one year after the shock, the accumulated effect eventually disappears.

Figure 5: Accumulated impulse-response path of the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic to one percent positive shock in the influx of remittances.

Considering the model with negative oil price changes, the Granger-causality Wald tests revealed that neither remittances nor negative oil price fluctuations Granger-cause changes in the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic. Thus, construction and interpretation of the corresponding cumulative IRFs cannot be implemented, due to the absence of any visible causal relationship among the aforesaid variables.

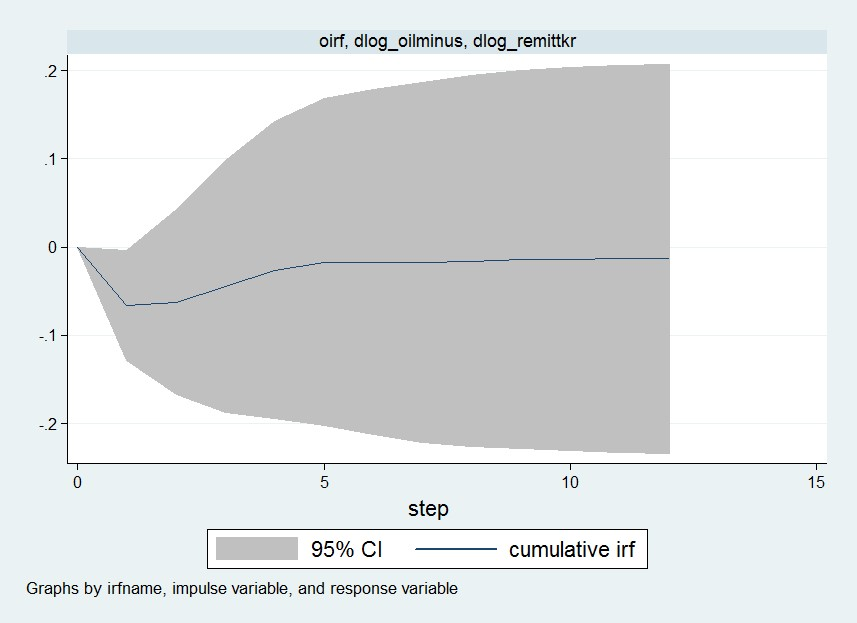

However, it was revealed that the influx of remittances is Granger-caused by the negative oil price changes, and thus is sensitive to them. Below, Figure 6 represents the accumulated impulse-response path of remittances to a one percent negative oil price shock. It is evident that the nature of the impact induced by the shock on the influx of remittances bears a transitory nature.

Specifically, in one month after the shock, the influx of remittances would decrease approximately by 0.066 percent. However, after the first month, the accumulated effect rapidly dies out, indicating that negative oil price shock would impact remittances only in the short-run.

In six months after the shock, the influx of remittances would decrease by about 0.017 percent, whereas in twelve months the impact would be even more negligent, equaling approximately to 0.013 percent decrease in remittances’ inflow.

Figure 6: Accumulated impulse-response path of the influx of remittances to one percent negative oil price shock.

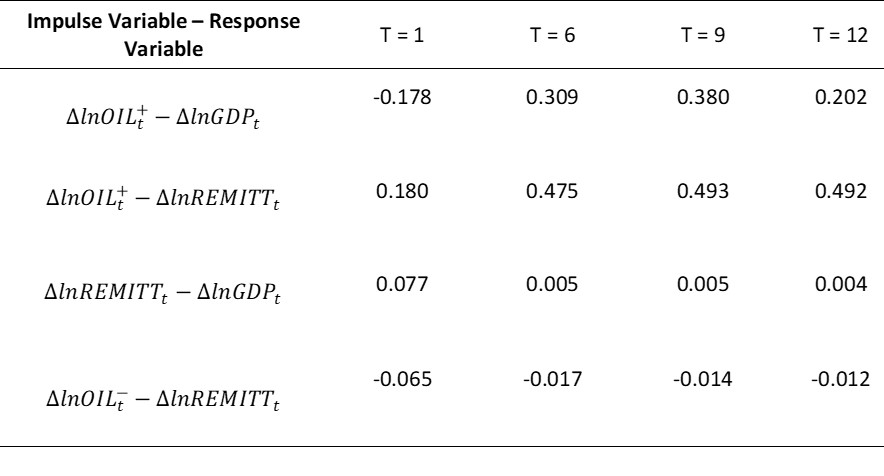

Figure 7: Accumulated response elasticities.

To summarize the results from the cumulative IRF analysis presented above, Figure 7 demonstrates the response statistics for each of the above-mentioned graphs. The first column of Figure 7 indicates the pair of impulse and response variables, whereas the first row highlights the corresponding time path. The internal part of Figure 7 is filled with the response elasticities, i.e. the percentage of change in the response variable caused by a one percent shock in impulse variable. As was previously mentioned, the dynamic system of VAR equations and the behavior of cumulative IRFs are sensitive to the specific order of the variables within each equation. Thus, as a robustness check for the proposed model and obtained results, it was decided to change the order of the variables within the dynamic system of VAR equations, further checking how a readjustment of variables would alter the behavior of the cumulative IRFs.

Figure 8 below summarizes the response elasticities for both models after an order readjustment was applied. As one may observe, the response elasticities have not demonstrated significant changes, preserving a similar trend of the response path. The similarity of the obtained results demonstrates an overall validity of the model and cumulative IRFs.

Figure 8: Accumulated response elasticities after order readjustment.

Conclusion

The peculiarities of the interaction between oil price shocks and economic growth cannot be considered insufficiently explored topics; there are numerous empirical inquiries devoted to the issue, covering different countries in various time periods, even taking into account the possibility of non-linear relationship.

Yet, there is still a shortage of empirical investigations on how the economic growth pattern of small oil importing economies from the post-Soviet region would react to a sudden change in the crude oil price.

The objective of the present study was to empirically explore how the economic growth in the Kyrgyz Republic would react to an unexpected oil price shock. The economy of the country incorporates a number of particular internal characteristics, i.e. the specific structure of the GDP, an unfavorable geographical position, and a strong economic influence from huge oil exporting economies. This, in turn, might completely transform the conventional way of how the small oil importing economy of the Kyrgyz Republic might react to abrupt fluctuations in crude oil prices.

Relying on the dynamic multivariate VAR methodology with corresponding derivation of Granger-causality Wald tests and cumulative impulse-response functions, it was revealed that only positive oil price shocks induce an effect on the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic.

Specifically, an immediate reaction of Kyrgyzstan’s real GDP to an abrupt oil price increase is negative. This fact does not support previously stated argument that economic growth of the Kyrgyz Republic should immediately benefit from a sudden hike in oil prices.

Our finding can be explained by the underestimation of the oil importing nature of Kyrgyzstan’s economy. Whereas service sector reserves the largest share of Kyrgyzstan’s GDP, industrial, agricultural and construction sectors are still dependent upon the supplies of energy products, and thus are sensitive to sudden fluctuations in crude oil prices.

However, in the long-term, the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic demonstrated an upwardly increasing pattern, proving that an abrupt increase in the oil price might benefit the real economic activity in Kyrgyzstan, yet not immediately and directly.

On the other hand, we found an absence of causality in terms of the effect of negative oil price shocks on the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic. The result was unexpected, as it was believed that negative oil price shocks should indirectly deteriorate the real economic activity of a small oil importing economy.

The acquired result might be explained by the overestimated roles of remittances, growth spillover effects and negative oil price fluctuations, as determinant factors of changes in the real GDP of the Kyrgyz Republic.

It has to be noted that the current empirical study incorporates a number of limitations, mostly with respect to the collected sample of time series data. Yet, despite of the existing limitations, the findings from the present research can be used for further investigations, as well as for the macroeconomic policymaking purposes.

Alan Mamatov holds MA degree from the OSCE Academy in Bishkek. He can be contacted by email: alan.a.mamatov (at) gmail.com

[1] Jiménez-Rodríguez, R., 2009. Oil Price Shocks and Real GDP Growth: Testing for Non-linearity. Applied Economics. 37(2). [Accessed 05 April 2016].

[2] EconPort, 2015. Supply and Demand Shocks. [pdf] Available at: <http://www.econport.org/content/handbook/Equilibrium/shocks.html> [Accessed 1 April 2016].

[3] EconPort, 2015. Supply and Demand Shocks.

[4] Jiménez-Rodríguez, R., 2009. Oil Price Shocks and Real GDP Growth: Testing for Non-linearity.

[5] Idem.

[6] The World Bank, 2014. Kyrgyz Republic: Overview. [online] Available at: <http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/kyrgyzrepublic/overview> [Accessed 22 June 2016].

[7] Central Intelligence Agency, 2015. The World Factbook: Kyrgyzstan. [online] Available at: <https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/kg.html> [Accessed 24 June 2016].

[8] Central Intelligence Agency, 2015. The World Factbook: Kyrgyzstan.

[9] The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2014. Kyrgyzstan. [online] Available at: <http://atlas.media.mit.edu/en/profile/country/kgz/> [Accessed 25 June 2016].

[10] The Observatory of Economic Complexity, 2014. Kyrgyzstan. [online]

[11] Ministry of Economy of the Kyrgyz Republic, 2016. Sotsial’no-ekonomicheskoe razvitie Kyrgyzkoy Respubliki. [online]

[12] Akmoldoev, K. and Budaichieva, A., 2012. The Impact of Remittances on Kyrgyzstan Economy. [pdf] Available at: <http://avekon.org/papers/534.pdf> [Accessed 25 June 2016].

[13] Budaichieva, A., 2012. The Impact of Remittances on Kyrgyzstan Economy.

[14] Faye, M. L., McArthur J.W., Sachs J.D. and Snow T., 2004. The Challenges Facing Landlocked Developing Countries. [pdf] Available at: http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/documents/JHD051P003TP.pdf [Accessed 26 June 2016].

[15] Sims, C. A., 1980. Macroeconomics and Reality. [pdf] Available at: http://www.jstor.org.ldb.osceacademy.kg:3020/stable/pdf/1912017.pdf [Accessed 25 October 2016].

[16] Jiménez-Rodríguez and Sánchez, 2004. Oil Price Shocks and Real GDP Growth. Empirical Evidence From Some OECD Countries. [pdf] Available at : https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecbwp362.pdf?b35d2a5fd0bae52378b274ce13a956c4 [Accessed 25 October 2016].

[17] Idem.

[18] Idem.

[19] Idem.

[20] Idem.

[21] Idem.

[22] National Bank of the Kyrgyz Republic, 2015. Statistics: External Sector of the Economy. [online] Available at: <http://nbkr.kg/index.jsp?lang=ENG> [Accessed 26 October 2016].

[23] StataCorp, n.d. Estimate the cointegrating rank of a VECM. [pdf] Available at: <http://www.stata.com/manuals13/tsvecrank.pdf> [Accessed 27 October 2016].

[24] StataCorp, n.d. Create and analyze IRFs, dynamic-multiplier functions, and FEVDs. [pdf]

[25] Idem.

Headline photo: Chunkurchak valley (Kyrgyzstan) by Irina Mironova